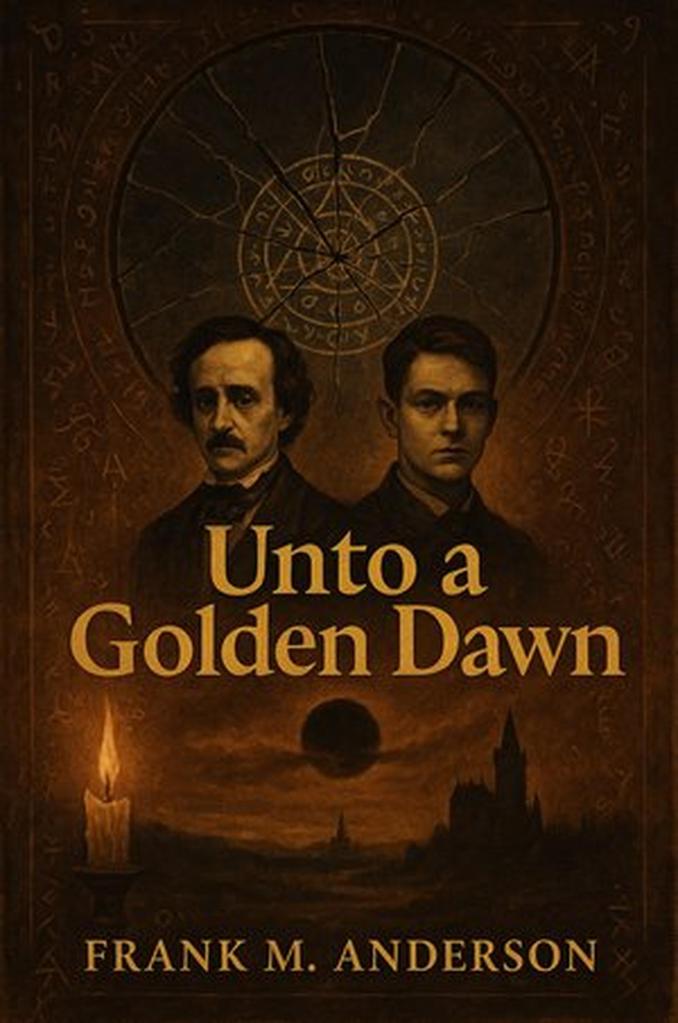

Aleister Crowley is one of those names that pops up in unexpected places—history books, occult manuals, heavy metal lyrics, even my own novel Unto a Golden Dawn. But why? What is it about this controversial figure that keeps him haunting stories, music, and imaginations?

The Boy Who Became “The Beast”

To understand Crowley, you have to start with the boy he was before the myth took over. Crowley wasn’t born “the wickedest man in the world,” as the British tabloids later called him. He was born Edward Alexander Crowley in 1875, into a strict, wealthy, and deeply religious family.

The bright spot in his early life was his father. Crowley idolized him. He felt seen, understood, and truly loved by him—something that would be taken away too soon. When Crowley’s father died of tongue cancer when Aleister was just 11, it left him shattered and unmoored.

All that remained was his mother’s harsh, judgmental presence. She called him “the Beast,” a cruel label meant to shame him. Instead, Crowley took the name to heart, adopting it as part of his identity—a twisted kind of armor. What started as rebellion against his mother’s religiosity and scorn became a lifelong war with the idea of “goodness” as he had been taught to see it.

I think this is the heart of Crowley: a child who never recovered from the loss of love and the absence of a guiding light. The rest of his life—the magic, the scandal, the wild pursuit of power and fame—feels like a boy trying to fill the void left behind.

Crowley’s Life and Legacy

Crowley was a poet, mountaineer, occultist, and founder of the spiritual philosophy called Thelema, which he summarized with the line: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” To some, this meant ultimate freedom to find one’s true purpose. To others, it was a rejection of morality itself.

Crowley became a legend by scandalizing polite society—posing in ceremonial robes, performing bizarre rituals, and writing cryptic texts that blurred the line between spiritual wisdom and provocation. Whether you think he was a genius or a fraud, Crowley’s life was a mix of brilliance, darkness, and relentless self-promotion.

Ozzy and “Mr. Crowley”

Fast forward to 1980. Ozzy Osbourne, the Prince of Darkness himself, releases “Mr. Crowley” on his debut solo album Blizzard of Ozz. The song isn’t about devil worship or blind admiration—it’s more like a conversation across time:

“Mr. Crowley, what went on in your head?

Oh, Mr. Crowley, did you talk with the dead?”

Ozzy wasn’t praising Crowley, but he was fascinated by him. He saw what I see: a man who lived on the edge of mystery, power, and madness. The song is haunting because it’s really asking: What did you find when you went so far? Was it worth it?

Crowley in Pop Culture

Crowley’s influence goes way beyond Ozzy:

- Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page was so obsessed with Crowley he bought the man’s old house on Loch Ness.

- David Bowie referenced him in lyrics as early as Hunky Dory.

- Iron Maiden and Black Sabbath both borrowed imagery from Crowley’s writings.

- Even modern shows like Supernatural and Good Omens nod to his legend.

Crowley has become shorthand for rebellion, mysticism, and dangerous charisma.

Why I Wrote Crowley Into My Book

In Unto a Golden Dawn, Crowley isn’t just there for shock value or historical flavor. He’s there because he represents a question I keep coming back to: What do we do with the power we’re given—whether that power is storytelling, influence, or just the way we shape the people around us?

I treat Crowley with kindness in the book, but not forgiveness. I see him as a broken, brilliant man who squandered his gifts on ego and spectacle. He sought to be known, not to protect or create. He became a legend but left little good in his wake.

In my eyes, Crowley’s life is a cautionary tale. He could have been something more—someone who used his influence to build, to uplift, to heal—but instead, he pursued power for its own sake. For that, I believe his death in obscurity was fitting.

Crowley as a Mirror

For me as a writer, Crowley also serves as a mirror. He reminds me of the dangers of creating for fame instead of meaning. He asks the hard questions about authorship and ego. In a recursive story like mine, where characters wonder who’s really writing their lives, Crowley becomes both a player in the game and a warning about the cost of forgetting what truly matters: goodness, love, and connection.

Final Word

In the end, Crowley is in my book not because I admire him, but because I want to face the shadows he represents—and rewrite them. He reminds me that brilliance without compassion rots into ego, that power without goodness turns hollow. By placing him in Unto a Golden Dawn, I’m not glorifying him. I’m challenging him—and, in some ways, challenging myself—to tell a story that chooses love, meaning, and survival over self-worship and spectacle.

Leave a comment