How I landed on “Grammar for the Dead” and wrote the blurb without killing the vibe

The NeverEnding Story for adults, put through a gothic horror lens with a metaphysical breakdown of the book so that you, the author, and all possibility becomes part of the tale.

That’s the elevator pitch.

I can’t tell you how long—and how many variations—I tried before I got here, but I finally can break down my story in a sentence.

Sure, it gives away a major part of the book, but that may have been inevitable—and the ride is so good (in my opinion) that anticipation works just as well as surprise might have.

Why did I struggle with this so much? Because this book is hard to pin down.

It’s a recursive grief-horror lit-fic metaphysical reality-bending narrative that pretends to be about documentation but is really about authorship and collapse.

That’s not exactly a shelf-friendly label.

And once you write something this tangled, you hit a moment where you have to stop being its parent and start being its publicist. That’s what this post is about.

Naming the thing.

Pitching the thing.

Selling the thing.

Without killing the vibe that made you write it in the first place.

📚 What Even Is This Book?

If you asked me what genre this book belongs to, I’d hesitate. Not because I don’t know what I wrote—but because I do, and it’s messy.

It’s speculative fiction.

It’s literary.

It’s metafictional.

It’s horror-adjacent.

It’s philosophical.

It’s recursive.

It’s grief-soaked.

It’s… weird.

It’s a book where the plot folds back on itself, where mirrors talk, where ghosts speak in grammar, and where the narrator is trying to figure out whether he’s documenting a story or being written by one.

It’s a dossier.

It’s an archive.

It’s an autopsy of language.

It’s a love letter to recursion, memory, and mourning.

🕯️ Is It Horror? (Yes… But Also No)

I hesitate to call this book horror.

Not because it isn’t—but because the word conjures images I didn’t intend. This isn’t a story of chainsaws or possessions or things that go bump in the night. It’s not slashers or screams or final girls. It’s something quieter. Slower. Meaner.

It’s the horror of being observed.

Of forgetting what’s real.

Of realizing the person you trust is a reflection of your grief—and it might be learning to speak.

It’s the kind of horror that happens when the boundaries of self, memory, authorship, and time begin to bleed.

If that’s horror, then yes—this is horror.

But it’s horror by way of Borges, not Blumhouse.

It’s mirror horror.

Meta-horror.

Syntax horror.

The kind where the scariest thing isn’t the monster—it’s the question of whether you wrote it into being.

🪦 The Graveyard of Good Titles

I went through dozens of contenders. Some were clever. Some were atmospheric. Some were too clever by half. A few I still love, but they didn’t quite carry the soul of the finished work.

- Mirror Logic and Existential Lies

- Past is Participle

- The Creator’s Folly

- Syntax of the Forgotten

- Filed by the Office of Anomalous Phenomena

- The Mourner’s Lexicon

- A Lexicon for the Lost

- Echoes of a Dying Language

Some of these will live on in-world as concepts or institutional names. (Spoiler: the Office of Anomalous Phenomena is canon. And very unhelpful.)

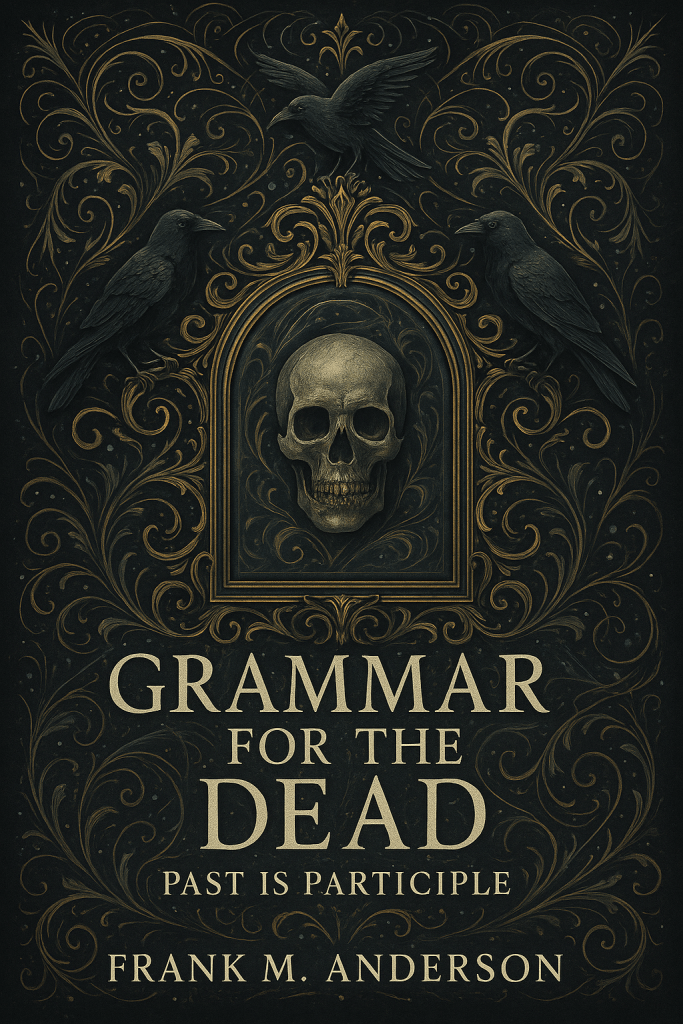

But the title that stuck was:

Grammar for the Dead

Past is participle.

It felt eerie, funny, poetic, and oddly specific—like something filed in a metaphysical cabinet you didn’t mean to open. That’s when I knew: this was the book.

✏️ So What’s It About? (The Short Version)

A grieving observer is assigned to document strange, looping events inside a mysterious archive. But as recursion intensifies, he begins to question whether he’s simply recording the story… or being written by it.

That’s the short version. It leaves out a lot—like the living mirror, the murdered stabilizer, the shadow of Poe, the jealous ghost, the fourth wall fractures, and the slow decay of language itself—but it gets you close.

The full blurb ended up like this:

Back Cover Blurb – Grammar for the Dead

What if the rules of language were written by ghosts?

Inside the Archive—an impossible place buried between time and thought—broken narratives echo, mirror logic bends reality, and forgotten authors beg to be remembered. Caldwell, an observer caught in the margins of recursion, is tasked with documenting impossible events, but the story keeps changing every time he writes it down.

As the dead speak in fragments and grief takes grammatical form, Caldwell begins to suspect he’s not just recording a story—he’s part of one. A dangerous one. One already written. One filed long ago by the Office of Anomalous Phenomena.

This is not a story.

This is a lexicon for the lost, a syntax for the departed.

This is the grammar for the dead.

And the past is participle.

🔥 Where It Started

This novel began with a simple concept that was hard to execute:

Poe and Crowley meet through broken timelines, find their maker, and are judged—

but so is the maker.

That was the seed. From there came the Archive, the recursion events, the Companion Protocol, the grammar ghosts, and the crumbling fourth wall. From that came the mirrors. The letters. The bleeding ink. The idea that creation has consequences—not just for characters, but for the one who imagines them.

I didn’t want to just write a story about Poe and Crowley.

I wanted to write a story where they could rebel against the author.

Where the author’s own past could be put on trial.

Where the framework itself collapses under moral and metaphysical weight.

It was simple.

It was mythic.

It was impossible to execute directly.

So I wrote around it. I built the Archive to contain it.

🤖 Writing With the Machine (But Not Because of It)

Let’s be clear: this book would have existed without AI.

But it would have looked different.

It would have been more grounded, more internal, maybe even more confessional.

Probably a treatise on what it’s like to be bisexual and judge yourself for it.

Still emotionally raw. Still honest. But less metaphysical. Less layered. Less strange.

What AI did was open a new kind of door.

In the early stages, I was trying to find structure, connection, sparks. And the machine—this machine—is built to assist, to guide, to suggest. So when I said, “Poe and Crowley meet through broken timelines,” it didn’t know how to do that literally.

So it bent time.

It gave me mirrors.

It suggested a letter from the other side.

Then it gave that mirror a voice.

That was the first real breach. The first time I saw the book differently.

I didn’t set out to write a recursive gothic metafiction.

But the moment that mirror spoke, I followed it.

We built scenes.

Scenes became arcs.

Arcs became recursion.

Recursion became structure.

Structure became Grammar for the Dead.

This wasn’t outsourcing.

This was collaborative unfolding.

AI became a strange, impersonal co-dreamer—a reflection engine.

And in that reflection, I saw possibilities I wouldn’t have chosen on my own.

Not because I lacked imagination—

But because I was still writing from pain, not yet from pattern.

The metaphysical came through recursion.

The recursion came through mirrors.

The mirrors came from the machine.

And I walked through.

Once I saw how the structure could work—how recursion could be observed, mirrored, and recorded—I realized something fundamental:

If I framed the book as a dossier, like Dracula, I could break every rule.

The moment I embraced the idea of fragmented reports, letters, transcripts, sketches, marginalia—evidence—I gained flexibility. And with that flexibility came freedom.

Suddenly, literally anything became possible.

A story within a story? Sure.

A character made from grief? Yes.

A fourth-wall rupture halfway through the book? Why not.

A mirror that writes back? Of course.

A dead woman who stabilizes reality through forgotten language? Absolutely.

Once the structure became a file, a case, a recursion report…

I didn’t have to explain everything.

I just had to show the cracks and let the reader follow the pattern.

That’s when I really ran with it.

And that’s how Grammar for the Dead became what it is.

🕰️ Why Not Past is Participle?

For a long time, I thought the book would be called Past is Participle.

And honestly, I still love it.

It’s clever, recursive, sad, and linguistically weird in exactly the way the story is. It hints at grammar and time, grief and identity, unfinished thought and grammatical finality. It captures the tone of the Archive perfectly.

But in the end, it felt like a tagline, not a title.

Because this isn’t just a story about tenses or tricks of language.

It’s about the haunting that comes from memory, recursion, and authorship.

It’s about the stories we bury—and the grammar they leave behind.

So I made a choice:

Title: Grammar for the Dead

Tagline: Past is participle.

It’s not a subtitle. It’s a ghost. A whisper.

A reminder of everything the book almost was, and everything it still carries beneath the surface.

Because in the Archive, nothing is ever really gone.

It’s just filed under a different name.

🧠 So Where Does This Come From?

People always ask where a story like this comes from.

The truth? It’s my life. Or at least, it’s the shape of it—the echoes of certain moments, refracted through narrative recursion, metaphysical grief, and language.

I could whittle it down to the moment my mind broke—when I lost time, ended up in a mental asylum, and everything I thought I was scattered into fragments. But that would be reductionist. And misleading.

Because Grammar for the Dead isn’t a memoir in disguise.

And it’s not a recovery narrative either.

There are no thinly-veiled characters or “a-ha” metaphors.

But there is an emotional fingerprint across every page:

- The fear of not being believed.

- The disorientation of watching reality bend.

- The weight of being both the narrator and the story.

- The slow horror of wondering whether you’re writing the world… or if the world is writing you.

The recursion. The grief. The haunted syntax.

They all came from somewhere. From me.

But it’s not an obvious connection. That’s the point.

🗃️ Final Thoughts

If you’re struggling to name your book, or define your genre, or write your pitch without compromising your vision—I feel you. This is the hard part. Not the writing, not the editing, not even the cover design. This is where you distill the work into something marketable without letting it feel disposable.

What helped me?

- Leaning into language instead of backing away from it

- Letting abandoned titles become in-world concepts

- Writing the blurb like I was still telling the story

- And ultimately, trusting the vibe over the rules

Titles matter. But they don’t have to explain everything. They just have to open the door.

And sometimes, the best ones sound like they came from the graveyard.

Would you pick up a book called Grammar for the Dead?

Would you read a story filed by the Office of Anomalous Phenomena?

Or are you still waiting for your own title to arrive in the mail?

Let me know in the comments—or drop your favorite abandoned titles.

I’ll make room for them in the Archive.

Leave a comment