The more I look at things, the more I realize that communication is our number one problem and our biggest benefit. We’re losing the ability to talk to each other — really talk — across lines of difference. We speak in rehearsed slogans, defend our tribes, and mistake volume for conviction. But if I could communicate one thing clearly, it would be that I still believe in democracy — and to me, that means people agreeing to take care of each other while allowing the best to rise to the top.

The point of everything, as I see it, is balance. And right now, we’re out of balance — socially, politically, spiritually. Democrats, especially in the South, have struggled to counter the right’s insistence that government itself is broken. We’ve played along with that story, maybe because things do seem broken at times. But the truth is, America is at its best when it creates space for everyone. We’re still trying to live up to that line about all men being created equal — and for all our chaos, we might be the closest any civilization has come.

I don’t believe in extremes. I believe in correction — in leaning toward what’s missing. And right now, what’s missing is understanding.

My Father, the Lawyer

My father was a lawyer, and as a kid, that meant one thing to me: Perry Mason.

I thought lawyers were heroes — men who fought for justice and used reason like a sword to carve order out of chaos. They didn’t fight for one side or another; they fought for truth. I loved that idea, that goodness itself could have a profession.

As I grew older, I learned all the jokes and stereotypes about lawyers. Greedy. Ruthless. Morally flexible. But none of that matched the man I saw coming home from work every night. My father could be tough — a bulldog, even — but I always felt there was a moral compass behind it, something steady and right that guided him.

Maybe that’s just how I wanted to see him. Maybe it was the truth. Either way, that picture has shaped me more than I realized.

Teaching taught me empathy. Writing taught me honesty. But my father taught me that goodness is worth fighting for — that you can live in a broken system without letting it break you.

War and the Lessons We Don’t Learn

Somewhere around the first Iraq War, I started realizing that the world I’d been taught to believe in — the one where good guys wore flags and bad guys burned them — didn’t line up cleanly with reality.

I remember the news clips of bombs lighting up the night sky like fireworks. People cheered, but something about it didn’t sit right.

By then I’d heard just enough about Vietnam to know that our stories about war aren’t always honest. That what we call “defending freedom” sometimes means defending interests. That sometimes the moral fight is just branding.

Don’t get me wrong — I still believe in a strong defense. I believe there are moments when force is necessary. But I also believe our greatest offense should be education.

If war is the machinery of destruction, then learning — curiosity, critical thinking, the willingness to listen — is the machinery of peace.

We spend billions on the tools that end lives, and almost nothing on the tools that expand them. If we put even half the reverence we give soldiers into teachers, I think we’d fight fewer wars to begin with.

The Wedge

College peeled back another layer.

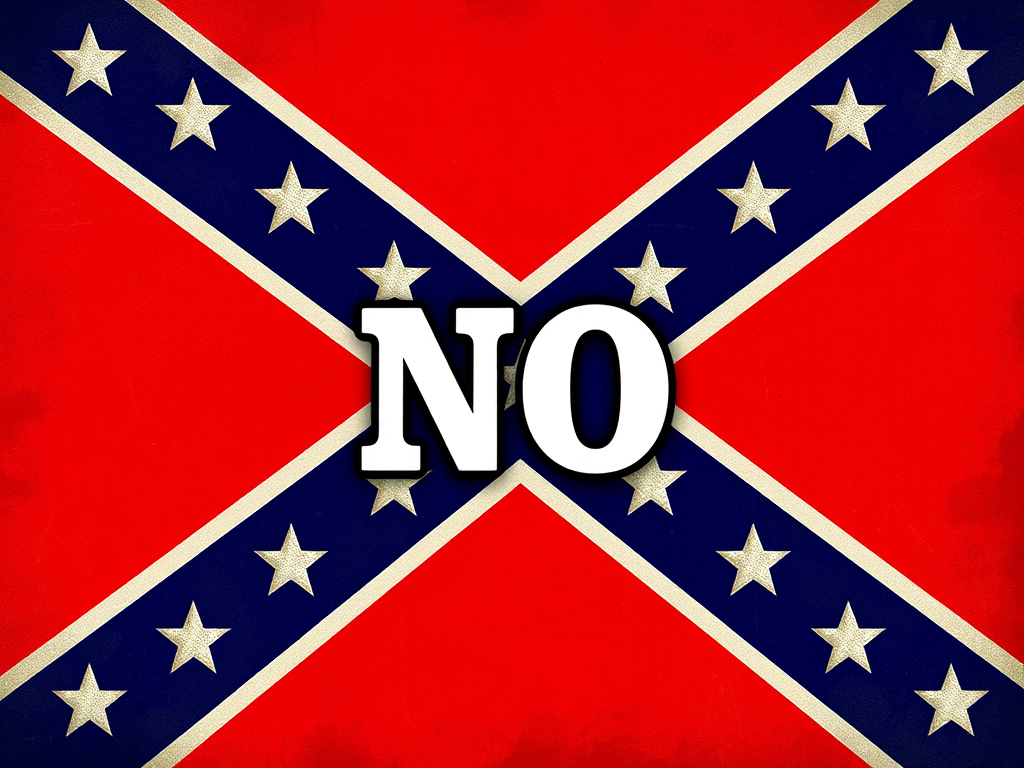

That’s where I learned about the Southern Strategy — how political operatives figured out they could use fear and social issues as levers to get people to vote against their own best interests. Race, religion, patriotism — all turned into tools for control.

It didn’t make me hate the South; it made me understand it. It helped me see how good people could be drawn into bad systems, how morality could be used like a fishing lure — shiny, emotional, and hooked from the start.

That’s when I began to see politics less as left versus right, and more as honest versus manipulative. The fight wasn’t between neighbors; it was between truth and whoever could profit from twisting it.

Manhood and Mercy

Part of why leftist ideas struggle in the South is because they’re seen as soft.

Compassion gets confused with cowardice. The idea that caring for people, or questioning power, somehow makes you less of a man.

But to me, the most manly instinct is the one to protect those with less power — not to dominate, but to defend. That instinct is written deep into us, but it gets twisted. Instead of guarding the vulnerable, we’re told to guard ourselves — to see every “other” as a possible threat.

That’s the trap of modern masculinity: mistaking fear for strength.

True courage isn’t about being hard; it’s about being open. It’s about taking chances on the belief that most people honestly want the best for themselves and for others.

That belief doesn’t make me weak. It’s the only thing that’s ever made me strong.

Guarded Cities

Greenville carries that same guardedness I see in so many Southern men. On the surface, we’re polite, hardworking, and proud of what we’ve built. But underneath, there’s a deep mistrust—of outsiders, of change, sometimes even of our own neighbors. You can feel it in the way people talk about “those parts of town,” or in how certain conversations go quiet when politics or race come up.

That kind of guardedness used to make sense. It was survival. People here learned not to trust easily — because trust had been betrayed plenty of times. But it also became a reflex, a habit we never unlearned.

I see that same reflex in our politics. We talk about strength, but what we mean is control. We talk about independence, but what we often practice is isolation. We call empathy weakness because we’re afraid of being hurt again.

But I think Greenville could lead the way in showing a different kind of strength. We’re big enough to hold differences, small enough to actually see one another. We could be a model for what happens when a city decides to listen more than it defends — when we stop treating understanding like surrender.

The same instinct that built mills and railroads and businesses — the instinct to protect and provide — could also build a more humane future, if we just turned it outward again, toward each other.

The Naïve Label

People sometimes tell me my beliefs are naïve — that I put too much faith in human goodness, or that I don’t understand how ruthless the world really is. But I’ve seen the ruthlessness. I’ve watched people burn out, break down, lose everything. I’ve seen selfishness win the short game.

And still, I don’t buy the idea that cynicism is wisdom. I think most people, deep down, do want the best for each other. We just get tangled up in fear — fear of losing, fear of being wrong, fear of being left behind. Fear is what sells. Hope doesn’t trend.

But hope is what keeps a democracy alive. Cynicism can’t build a bridge; it can only tell you why it’ll never stand.

So call me naïve if you want. I’ll take it as a compliment. Naïveté, in a world addicted to outrage, might be the last honest form of courage.

The Long Conversation

If I had to sum it all up, I’d say this: I’m a Southern leftist because I still believe in people — even when it’s hard to.

I believe that communication is how we save each other, that democracy only works when it’s rooted in care, and that education is the quiet revolution that keeps us from repeating the same old mistakes.

I believe the South is capable of more than the world gives it credit for — that under the bluster and bravado, there’s still a deep current of decency running through us. You can see it in the way we show up when someone’s house burns down, or how we’ll give a stranger the last biscuit on the plate. That instinct to care is what I want to build on.

To me, being Southern isn’t about preserving the past; it’s about wrestling with it honestly and still finding a way forward. Being leftist, in my sense of the word, isn’t about tearing everything down — it’s about widening the circle of who belongs.

So no, I don’t believe empathy is weakness. I don’t believe fairness is naïve. I don’t believe the best days are behind us.

I believe we just stopped listening long enough to notice how much we still have in common.

The South isn’t one thing — it’s a long conversation. And I’m still talking.

Leave a comment